I like ferns. Whenever I am at a botanic garden, I take a close look at them. I love the elegance of the leaves (fronds), the way the fronds unfurl, and the polka-dot patterns of the sori (spore cases) on the underside of the fronds.

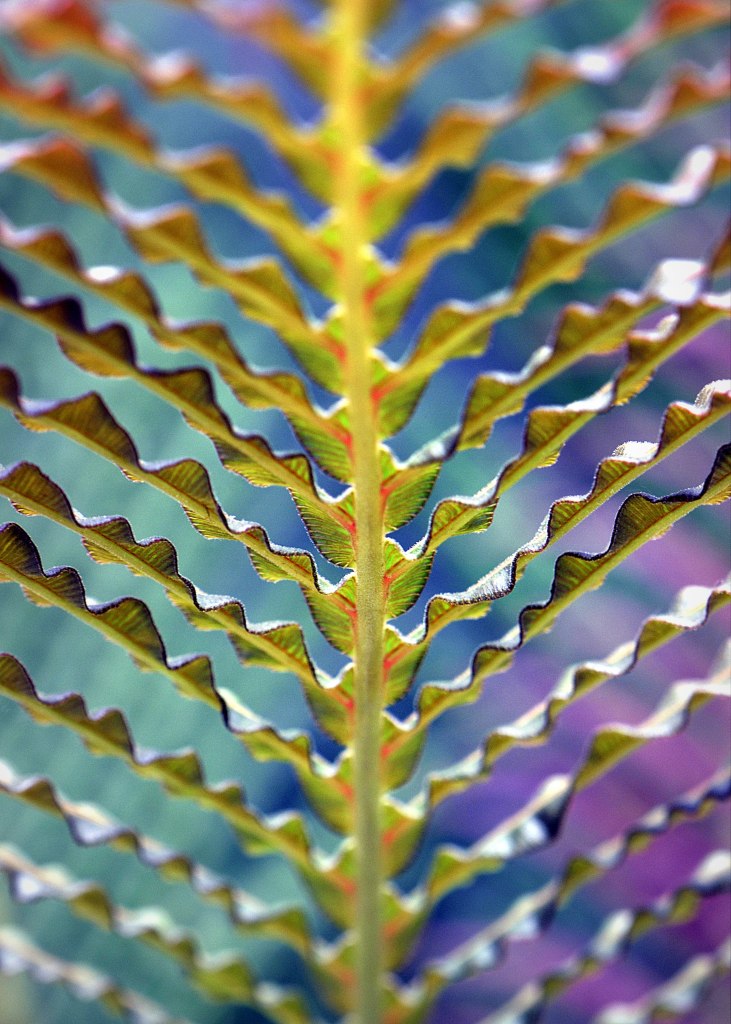

During the recent winter holidays, we went to the Garfield Park Conservatory in Chicago — a magical place any time of the year, but a fantastic one to visit during the colder months. My attention was caught by a fern I had never seen before, with an intriguing leaf pattern:

This fern is called a Microsorum musifolium (or Polypodium musifolium). ‘Microsorum’ means ‘small sori’ and ‘musifolium’ means ‘banana-like leaves,’ because of the fern’s long, strap-like leaves. ‘Polypodium’ means ‘many-feet’ and refers to the growth pattern of the fern’s underground, horizontal stems (see the lithograph at the bottom of this post).

In recent years, this plant has also become known as a Crocodile Fern because some people think the texture and pattern of the fronds looks reptilian. (And because some clever house-plant marketers decided “Crocodile Fern’ would sell better than, say, ‘Banana-Leaf Fern’ — or worse, ‘Wart Fern,’ as it is sometimes also called.) Because of this new-ish twist on the plant’s name, it is now common to see the fern [mis]labelled as Microsorum musifolium ‘Crocodylus,’ the latter part of which signals an animal genus, not a botanical one.

I don’t have any crocodile photos, but I do have some close-ups of an alligator’s back. And while I can see that the fern does look reptilian in a way, it may be a stretch to say it looks like the patterns on the back of a crocodile (or alligator):

Common names aside, the fern is native to Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands, and is an epiphyte; it grows on trees for support but it does not take any nutrients from them. Instead, it forms a half-basket against the tree trunk that catches falling leaves and debris, which give the plant moisture as well as nutrients as the leaves and debris decompose. As a houseplant (ie, when it is not tucked against a tree trunk), the fern will form a full, circular basket. Plants that do this — including Bromeliads — are called ‘trash-basket plants,’ which is not the nicest name for a great adaptation. Luckily, many ferns in this category are called Bird’s Nest ferns, which sounds much better.

Microsorum musifolium was first described by the German-Dutch botanist Carl Ludwig Blume in his famous 19th-century work, Flora Javae (Plants of Java), written after he had served as a director at the botanic garden in Bogor (then known as Buitenzorg), Java. There is some confusion over when, precisely, Flora Javae was published, as different sections were added between 1828-1858.

I saw a hand-colored lithograph of ‘Polypodium Musaefolium’ attributed to Blume’s 1829 edition of the book for sale online, and wanted to confirm that it was, in fact, from that book (not that I wanted to buy it; I just wanted to know when the fern was first mentioned). I looked at the list of sections added to Flora Javae over the years, which notes all the ones added in 1829, but there were no sections called Polypodium or Polypodiopsida. I wondered if ferns were called something else back in the day. Sure enough, ferns were traditionally classified as Filices — and that was the title of one of the 1829 sections. So I knew Blume had devoted a sizeable section of Flora Javae to ferns, and I hoped Microsorum musifolium was among them.

Motivated by this discovery, I kept looking and — amazingly — found a full-text 1858 version of Flora Javae, thanks to the Biodiversity Heritage Library; it is from an edition held by the Peter H. Raven Library at the Missouri Botanical Garden. The 1858 version includes all the sections added previously, including the one on ferns. I searched the text for ‘Microsorum musifolium,’ but no luck. Then I remembered Blume’s lithograph was labeled ‘Polypodium.’ That worked; there are a LOT of Polypodium entries in Flora Javae. But the search did not turn up any entries for Polypodium musifolium or musaefolium (at the time, I did not realize that this result – POLYPODIUM MUSffiF0LIU3L — was the one I was looking for). So I tried to scroll through all the entries manually to find it . No luck, again. Until I came across another clue: the lithograph was described online as being Tab. LXXIX, and using that as a guide, I finally found the entry for ‘Polypodium Musaefolium’ on pp. 171-72 of Flora Javae:

And there you have it. Should you be lucky enough to see this unusually patterned fern in a botanic garden, or grow it as a houseplant, you will be able to say it was first immortalized in print almost 200 years ago! And that it kind of, sort of — from a certain angle and at a certain distance — could resemble a crocodile’s back.