There are certain plants with pointy pinnate leaves (ie, leaves connecting to the stalk like quills on a feather) that look very alike, even though they are not at all related: cycads, palms, and ferns. For one, they evolved millions of years apart. Ferns, which reproduce by dispersing spores, appeared at least 360 million years ago, long before seed-bearing plants. Cycads are among the earliest of the seed-bearing plants and have been around for about 280 million years. The evolution from spores to seeds was one of two dramatic land-plant developments. The other was the emergence of flowers about 100 million years ago, after which palms arrived on the scene. At a mere 60 million years old, palms are botanical babies compared to the other two, though all three shared time and space with dinosaurs.

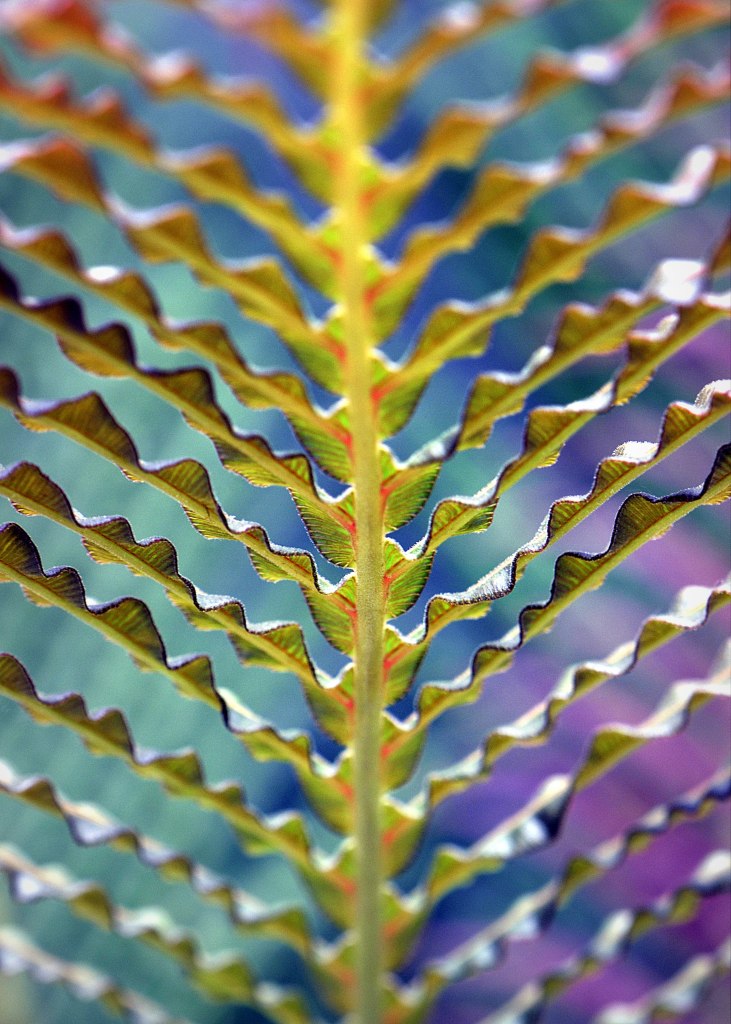

There are many ways to tell the three plants apart. Cycads and palms have woody trunks; ferns do not. And fern fronds are much softer and more delicate than stiff and spiky palm fronds or cycad leaves (some of which look positively lethal):

Distinguishing between cycads and palms can sometimes be tricky as they both have crowns of pointy leaves atop a woody trunk. For a while, I assumed if it was tall and tree-like, it was a palm, and if it was closer to human height and a bit bushier, it was a cycad. Then I saw the Albany Cycad at the San Diego Zoo (at 500 years old, it is the Zoo’s oldest plant); it is taller than I am and looks a lot like a palm tree.

But there is a way to tell tall cycads and palm trees apart: look at the trunks. Cycad trunks are rough and stocky while palm trunks are slimmer. Also, while both plants have scarring on their trunks where the leaves have fallen off, cycad leaf scars appear in a spiral pattern, while palm leaf scars often look like rings around the trunk. So if you see ringed scarring on a tall and elegant trunk, that’s a good clue that you are looking at a palm and not a cycad.

Another difference is that cycads are gymnosperms and palms are angiosperms, but those terms aren’t very helpful unless you know that gymnosperms = cones, and angiosperms = flowers and fruits. So if you are looking at an as-of-yet-unidentified plant with stiff and spiky pinnated leaves and see a cone at the center of those leaves, it’s a cycad. And that cone is why cycads are most closely related to conifers.

If you see any flowers at all (or fruits such as coconuts, dates, or berries), it’s a palm. Ferns are neither gymnosperms nor angiosperms; they are primordial, vascular plants and do not produce flowers, fruits, or cones. So if you are looking into what you think is a clump of ferns and see a cone, it’s not a fern. If you see a woody trunk, it’s also not a fern. But, if you see spores on the underside of the fronds, it IS a fern!

Finally, a word about Sago Palms, a group of palm-like plants that are actually cycads. They got their name because way back when, someone else had a hard time telling them apart. (So glad I am in good company.)

A final twist to this tale: though cycads can look like palms, their young, emerging leaves look remarkably similar to unfurling fern fronds. I don’t have a photo of a cycad leaf unfurling (unfortunately), so the first photo below is kindly borrowed. I’ve added a fern photo I do have for comparison. One could easily be forgiven for mistaking an unfurling cycad for a fern. But take a careful look at the rest of the plant. Touch the mature leaves to see how hard or soft they are and whether there are any spores underneath, see if there is a woody trunk (if so, look at leaf scarring), check for cones or fruits. All those things will point you in the right direction.